| Product Code: | EMA 759 |

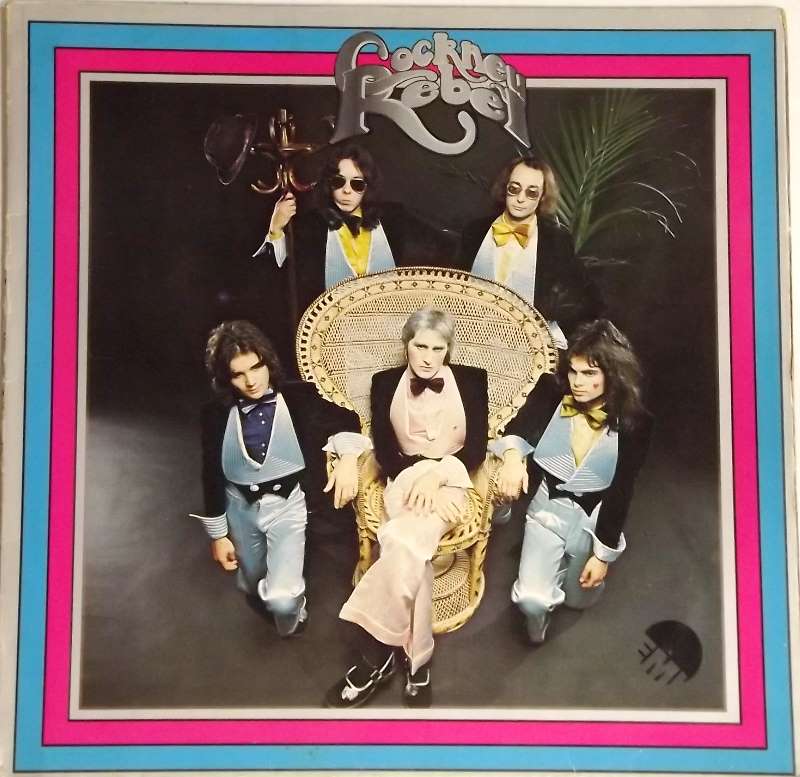

| Artist: | Cockney Rebel |

| Origin: | England |

| Label: | EMI (1973) |

| Format: | LP |

| Availability: | Enquire Now |

| Condition: |

Cover: VG

Record: VG+

|

| Genre: | Rock U |

Good clean vinyl, nice cover with minor shelf wear.

Indulging for the first time in Cockney Rebel's debut album -- and one uses the word "indulging" deliberately, for like so much else that's this delicious, you cannot help but feel faintly sinful when it's over -- is like waking up from a really weird dream, and discovering that reality is weirder still. A handful of Human Menagerie's songs are slight, even forced, and certainly indicative of the group's inexperience. But others -- the labyrinthine "Sebastian," the loquacious "Death Trip" in particular -- possess confidence, arrogance, and a doomed, decadent madness which astounds. Subject to ruthless dissection, Steve Harley's lyrics were essentially nonsense, a stream of disconnected images whose most gallant achievement is that they usually rhyme. But what could have been perceived as a weakness -- or, more generously, an emotionally overwrought attempt to blend Byron with Burroughs -- is actually their strength. Few of the songs are about anything in particular. But with Roy Thomas Baker's sub-orchestral production driving strings and things to unimaginable heights, and Cockney Rebel's own unique instrumentation -- no lead guitar, but a killer violin -- pursuing its own twisted journey, those images gel more solidly than the best constructed story. The Human Menagerie is a dark cabaret -- the darkest. Though Harley has furiously decried the band's historical inclusion in the glam rock pack, there's no separating the nocturnal theatrics of "Muriel the Actor," "Mirror Freak," or "What Ruthy Said" from at least the fringes of the movement. The difference is, other artists simply sung about absinthe and Sweet Ipomoea. Harley actually knew what they were. Unquestionably, he drew from many of the same literary, artistic, and celluloid sources as both David Bowie and Bryan Ferry, the only performers who could reasonably claim to have preempted his vision. But he went far beyond them, through the Berlin of Isherwood to the reality of the Weimar; past the Fritz Lang movies which everyone's seen, to the unpublished screenplays which no one has read. And though Harley might not have been the first cultural genius of his age, he was the first who wasn't content to simply zap the prevailing zeitgeist. He wanted to suck out its soul. And he very nearly succeeded.