| Product Code: | 9029527215 |

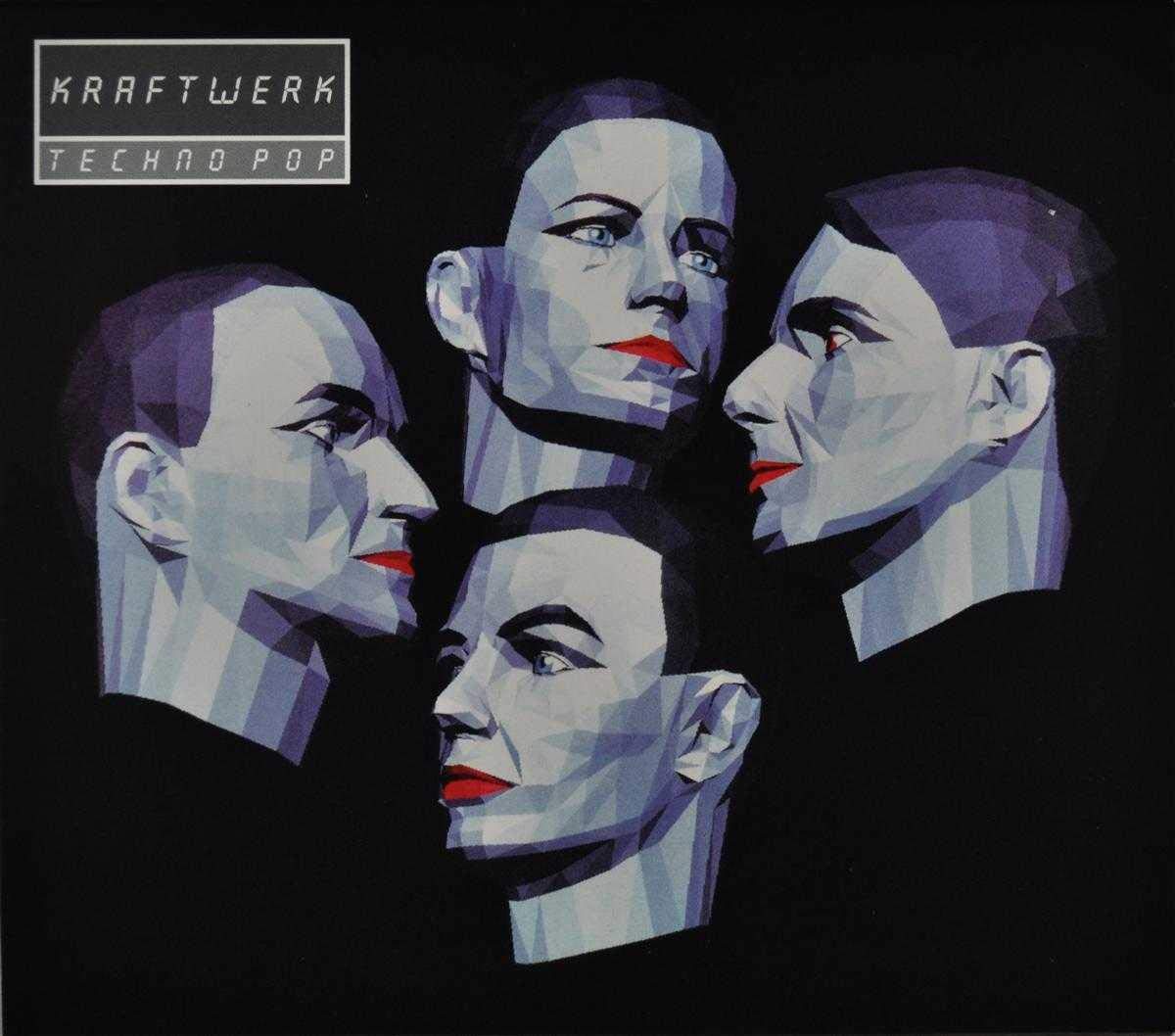

| Artist: | kraftwerk |

| Origin: | EU |

| Label: | Kling Klang (2020) |

| Format: | LP |

| Availability: | In Stock |

| Condition: |

Cover: M

Record: M

|

| Genre: | Electronic , Krautrock N |

Brand new sealed LP, Album, Limited Edition, Remastered, Special Edition, Stereo, 180g, Clear Vinyl.

Despite an album entitled Techno Pop appearing in the EMI release schedule for 1983, the Tour de France EP turned out to be the only Kraftwerk release that year. There would be nothing but silence until 1986 – five years on from Computer World – when the album Electric Cafe finally emerged. Debate raged for many years about whether this was in fact a reworked version of Techno Pop, or if there really was some Great Lost Kraftwerk album mouldering in an archive somewhere.

When Electric Cafe was reissued on CD in 2004 with the name Techno Pop it put an end to such speculations and confirmed the sorry truth: Techno Pop had been recorded and slated for release in 1983, but a crisis of confidence - as well as a serious cycling injury sustained by Ralf Hütter - had seen its release postponed. After the album had been mixed in New York none of the band was happy with it, and the decision was taken to scrap it and start again. The change of name to Electric Cafe was presumably born of embarrassment that even as fastidious a group as Kraftwerk had taken the best part of five years to produce 35 minutes of music. And not very good music at that.

Or so went the critical judgement of the time as far as the last point is concerned. In truth Techno Pop suffered from following on from three instant classics, as well as from the huge leaps in production capability that had taken place in the years following Computer Love. You no longer had to dedicate months and years to infusing electronics with human warmth and uncanny funk: you could buy a Roland 303, 606, 808 or 909 for less than $1000 and, with some talent and gumption, start kicking out house and techno jams with production values that just a few years before would have been unthinkable without the resources of a powerful studio to draw on. Kraftwerk had never felt threatened by the synthpop groups, or “that silly English pop scene, with silly lyrics”, as the group’s Karl Bartos put it, but when they went to New York to mix Techno Pop the music they heard being played in the clubs intimidated them.

As one writer put it in 1985, Kraftwerk were now operating in a world “that had largely embraced and vindicated their social and musical visions.” But rather than soak up the adulation they retreated from the world and remained in the fastness of their Kling Klang studio. As the band’s biographer Pascal Bussy describes, when Michael Jackson called them in 1985 or 1986, asking for permission to use the master-tapes of ‘The Man-Machine’, the answer was a polite but firm no.

When you listen to Techno Pop without the expectations of five years of keen anticipation pressing down on the needle, though, it’s possible to discern the record’s not inconsequential merits. The opening trio of songs, which is really one extended track in the manner of ‘Trans-Europe Express’/‘Metal on Metal’/‘Abzug’, is a flawed masterpiece of powerfully monomaniacal rhythmical development. ‘Boing Boom Tschak’ is a Dadaist construction in the manner of Kurt Schwitters’ sound poems, the vocal approximations of drumbeats becoming percussive elements of the beat itself. This wasn’t revolutionary by any means – it’s basically what any chopped-up vocal sample in a house record does – but the ceaseless flexing and convolutions of the track’s beat pattern is a superb work of electronic sound manipulation.

‘Boing Boom Tschak’ flows directly into ‘Techno Pop’, which is the first Kraftwerk track that could be described as even remotely meandering since ‘Morgenspaziergang’ closed Autobahn back in 1974. Momentary desultoriness aside, the title track’s final third snaps back into focus, a scything low-end synth line moving beneath delicate synthesised marimba and xylophone patterns like a circling shark. This intensity is maintained by ‘Musique Non-Stop’, which might leave lovers of Kraftwerk’s songcraft unmoved but represents an excellent example of their ability to create rhythm tracks that are all the more enthralling for being so spartan.

Outside of the metallic carapace of this opening salvo, things become less focused. ‘The Telephone Call’, Karl Bartos’s only moment on the mic, is a very catchy pop song but underlines the fact that Techno Pop-vintage Kraftwerk doesn’t sound like the future: it sounds exactly like 1986. Interestingly the original and 2004 reissue of this album featured an eight-minute version of ‘The Telephone Call’, but the present remaster (which sounds only marginally sharper than the original album, which was Kraftwerk’s first digitally recorded album) features the single edit. An extra track, ‘House Phone’, has been added. Originally on the 12” single release of ‘The Telephone Call’, it’s a fairly undistinguished instrumental which, I can only surmise – and it makes me sorry to think so – has been added as bait for completists.

Sounding even more 1986 than ‘The Telephone Call’ are the melodramatic strings, guitar and slap bass on the (I think) intentionally hilarious ‘Sex Object’, on which Ralf Hütter scolds an unnamed other for wanting him only for his body. All the ‘real’ instruments are in fact synthesised approximations and I admit it might be a personal thing, but I’m constitutionally incapable of coping with slap bass outside the confines of a Parliament Funkadelic record. If techno, according to Derrick May’s famous definition, was the sound of Kraftwerk and George Clinton trapped in an elevator with nothing but a sequencer to occupy them, then ‘Sex Object’ is what happened when Clinton got swapped out for Mark King.

Ending with the lacklustre ‘Electric Cafe’, Techno Pop can only be viewed as a failure, despite the fitful brilliance of its opening section. The disappointment is all the more keen when it's viewed as part of a continuum the three previous instalments of which proved to have such a radical and widespread effect on late-20th century music. It’s also telling that this was the first Kraftwerk album since 1973's Ralf and Florian that wasn't dominated at least in part by an overarching theme. Conceived in an atmosphere of negativity and self-doubt, it's difficult to escape the conclusion that these unwelcome elements had infected the album's unhealthily long gestation.