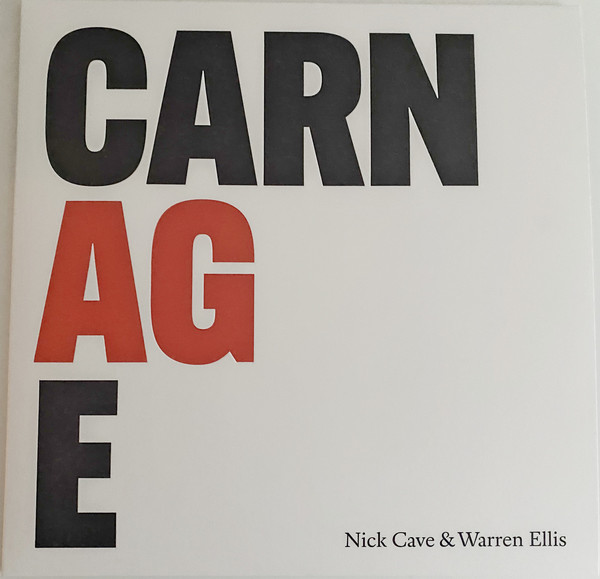

| Product Code: | BS021LP |

| Artist: | Nick Cave & Warren Ellis |

| Origin: | EU |

| Label: | Goliath Records (2021) |

| Format: | LP |

| Availability: | In Stock |

| Condition: |

Cover: M

Record: M

|

| Genre: | Art Rock , Electronic , Rock N |

Brand new sealed zlbum. Includes a 24-page, 12x12 booklet and printed inner sleeve.

Front cover has embossed lettering CARNAGE.

Nick Cave’s cinematic work with his bandmate Warren Ellis is a slight departure from last decade’s trilogy of albums. It’s defined by its stark contrasts, at turns brutal, surreal, and romantic.

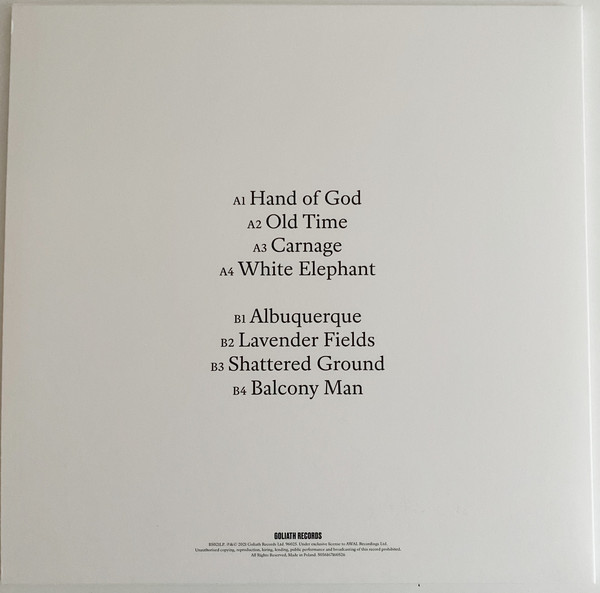

Nick Cave sings, “This song is like a rain cloud that keeps circling overhead,” and then pauses before delivering the next line: “Here it comes around again.” This is “Carnage,” from the album of the same name, the first release credited to the duo of Cave and his longtime Bad Seeds bandmate Warren Ellis, aside from their prolific output of film scores. Just before observing the impending storm in his own music, Cave has been sitting on a balcony, perhaps outside a hotel room where a woman sprawls lazily across the bed. (We’ll find him back there later.) The balcony is one of many motifs that recur and refract across Carnage: some bags thrown in the back of a car, a Glen Campbell song, strange creatures by the side of the road, and above all, “that kingdom in the sky.” Together, these repetitions contribute to the sense that the album is less a collection of discrete songs than one long rumination in eight stages—or a circling rain cloud, coming around and around again.

Carnage comes after a remarkable trilogy of Bad Seeds releases, in which Cave and his band—among the fiercest animals in rock’n’roll, when they want to be—approached total stillness. By 2019’s Ghosteen, there were no drums and few recognizable rock instruments. Cave’s formerly narrative songwriting became impressionistic and autobiographical, sometimes seeming to embody the mysteries of life itself. Over crystalline loops of electronics and piano, he reckoned in piercing detail with the death of his teenage son Arthur in 2015, and his own search for redemption in the aftermath. It was, along with everything else, a pinnacle of his artistry, 40 years in. As a musician and as a person, where does one go from there?

For Cave and Ellis, the solution was to jettison even more cargo. They may have created Carnage as a duo partly out of pandemic necessity, but shedding the band also made good creative sense. Given the Bad Seeds’ recent trajectory, and the paring down of personnel, you might expect further exploration of Ghosteen’s meditative minimalism, and at times that is essentially what Carnage delivers. But in its most gripping and audacious moments, the album is much wilder than its predecessor. It draws from the formal language of modern cinema, concerned less with verses and choruses than images, settings, visceral portrayals of extreme emotional states. It begins on a smash cut, with a few lines of a stately Boatman’s Call-style piano ballad interrupted by a dissonant swirl of strings or electronics and an insistent mechanical pulse. Mid-lyric, Cave’s measured vocal takes on a note of terror, as if the floor opened under him and he’s tumbling into a bottomless hole of the mind.

Cave has always been attuned to the power of artifice and character, but here, more than ever, he is acting as much as singing. When he’s not delivering outright spoken monologues, he’s sticking to handfuls of close-by notes, relying on inflections of speech rather than melody for expressiveness. The most memorable part of a given line might be the implied threat beneath the force of this or that syllable, or the anxious way he draws out a particular “uhhh.” If you come to Carnage expecting the conventional virtues of rock or pop, even of Cave’s own earlier work—riffs, tunes, grooves, and so on—you will likely be disappointed. Even for those who enjoy the album, it may be hard to imagine listening particularly often. But, as is the case with plenty of great films, replay value seems beside the point.

Carnage has no plot per se, but its motifs gather force as they pile up and interact, such that listening out of order would do the album a disservice. The story they tell is a version of the one Cave has spent his whole career telling, before and after the tragedy that ruptured his personal life—about our equal capacities for cruelty and love, and the flickering possibility of salvation in a brutal world. “By the side of the road is a thing with horns/That steps back into the trees, and a child is born,” he declaims on “Old Time,” whose throbbing bass and slashes of guitar provide some of the album’s purest musical thrills. In “Carnage,” one song later, “a reindeer frozen in the footlights steps back into the woods.” Of course, headlights are what we generally picture freezing deer in their beams; footlights are more likely to illuminate performers at a theater. That sly inversion reaches back to touch the previous song, and we wonder if the child-giving horned creature by the road is a version of the singer himself.

As ever, Cave uses overtly religious imagery in ways both subversive and devout. The “kingdom in the sky” first appears in the album’s opening lines, where the foreboding music suggests we are doomed never to find it. Its final recurrence comes near the album’s end, in the dreamlike “Lavender Fields,” where a choir urges Cave’s narrator to have faith despite his loss: “Where did they go?/Where did they hide?/We don’t ask who/We don’t ask why/There is a kingdom in the sky.”

The kingdom appears most memorably between these poles, in the delirious coda to “White Elephant,” the album’s centerpiece. Over a sinister rhythm track that nearly scans as hip-hop, Cave gives a thunderous monologue in character as a sort of spiritual embodiment of white supremacy. As protesters tear down statues, his boasts become increasingly deranged. Then a drum fill and another jarring smash cut, this time to a drunken gospel-rock singalong, equally jubilant and grotesque: “The time is coming, the time is nigh/For the kingdom in the sky.” God is many things to many people, this passage suggests, and not all of them good. The album’s catchiest hook becomes an arch conceptual set piece, more unsettling than uplifting.

If Carnage’s feverish first half sometimes recalls David Lynch, its austere second is more like Terrence Malick. After “White Elephant,” the album settles into an extended comedown, both musically and lyrically. The abrupt tonal shifts recede in favor of Ghosteen-ish washes of placid harmony; Cave’s focus zooms out beyond the pained countenances and rictus grins of Side A to encompass entire cosmic landscapes. The second act is slightly less satisfying than the first, if only because it’s more clearly an extension of the last few Bad Seeds albums. But in the world of Carnage, these final four songs offer a tentative but hopeful resolution to the initial chaos. It culminates with a return to the balcony, on a morning with no storms in sight, for now. “There’s a madness in her and a madness in me/And together it forms a kind of sanity,” Cave sings atop drifting synthesizers on “Shattered Ground,” a couplet that should resonate with anyone who has passed through trouble with a partner only to find more on the way. The next line comes as a surprise every time I hear it, with a sudden, choked, almost accidental directness that only heightens its power and apparent centrality. Everything is in those five words: “Oh, baby, don’t leave me.”