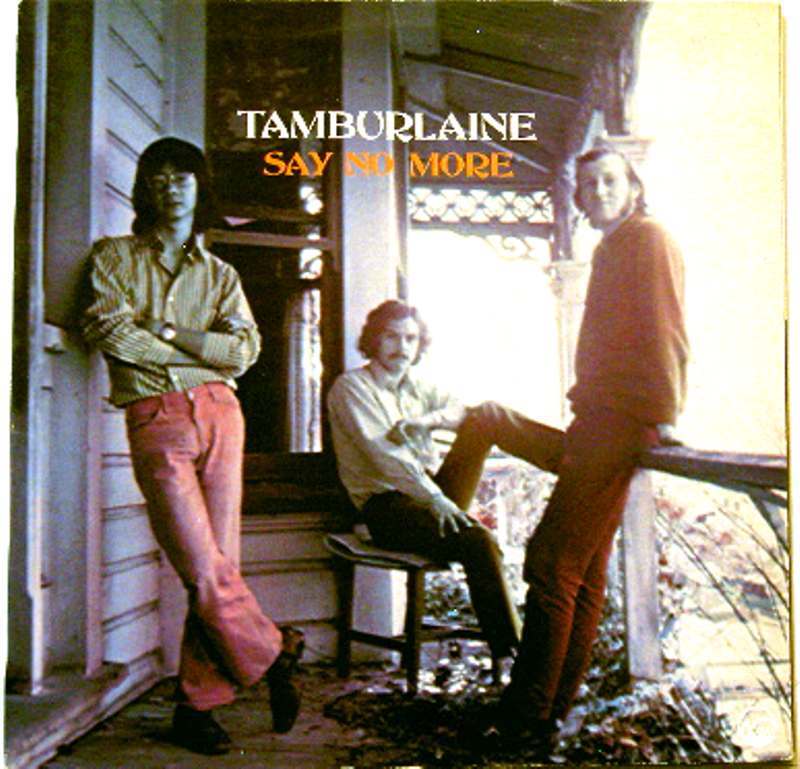

Mega rare debut album by New Zealand psychedelic folk band, smart vinyl, gloss gatefold cover..

Raised in Wellington’s rich musical underground, the great Tamburlaine was born from British-style blues and the folk revival, and graduated from shouty, sweaty clubs to spellbinding larger concerts.

Guitarist Steve Robinson grew up in Fiji, where he studied piano from age four, played the violin in school orchestras and learned the ukulele, which naturally led to guitar. Returning with his family to New Zealand as a young teenager, he first played bass in Christ College’s ironically named beat covers band The Pagans, and later, lead guitar with Wellington College’s Us Five.

Long before graduating to guitar, young Denis Leong studied piano for eight excruciating years, while also developing his singing voice. Backed by brother Kevin on guitar, Leong sang and together the brothers dominated 1950s talent shows, where they regularly won prizes in competition and accumulated a modest collection of toasters and other small kitchen appliances.

“I would like to say we sang early Chuck Berry or Everly Brothers tunes,” says Denis Leong, “but … our repertoire was limited to all but the cheesiest of top twenty hits.”

Meanwhile, bassist Simon Morris was playing lead guitar in his Onslow College school band Changing Times when formidable future vocalist Rick Bryant tried out for singer, but was turned down. Meeting up again with Morris at university, a newly honed Bryant fancied starting a “serious blues band”, and he and Morris bore Original Sin. “Original Sin was very much a bunch of mates into Chicago type blues (Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, etc.), pretty much driven by Rick," says Steve Robinson.

After unshackling from Rick’s harmonically-challenged brother Rod on mouth harp, the Sin really caught fire when ex-Canberran draft-dodger Bill Lake took on guitar and harmonica. Cafe L’Affare founder Jeff Kennedy played drums, rounded off, says Morris, with “a revolving door of bass-players. We could never hold onto one. Steve Robinson was one, Tony Backhouse another, [and] Lindsay Field [later an in-demand backing vocalist in Australia]."

“I went to see Original Sin perform in a school gym,” says Denis Leong. “The stage was full but the hall was empty and there was possibly just one functional amplifier. I was there because Rodney Bryant – a year younger at Rongotai College – claimed to play in a rock band. A group of fellow sixth-form skeptics went to check this out. While Rodney did not play, his older brother Rick did, ably fashioning a credible Chicago blues frontman persona in the manner of a prematurely weathered Van Morrison. More striking was another fellow who did all the talking bits between songs. This fellow told great jokes and projected a very sunny entertaining disposition … a touch at odds with the otherwise grim authentic blues ethos. That was Simon.”

Sure, Original Sin had started off playing “authentic” blues – via the Stones and The Pretty Things – but soon the Sin stepped even farther from the source when Hendrix and Cream modified the mix. Songs got longer, tempos and keys changed more, and there was more adlibbing and improvisation.

They played sporadically – including a gig for the Karori Girl Guides – and by 1968 they were the resident band at the Mystic, on Wellington’s Willis Street, a hot, smoky blues club with ultraviolet lighting.

In 1971 Tamburlaine was performing around Wellington with similarly progressive folkies at the university and Chez Paree. “I vividly remember coming off the stage in the Victoria University Union Hall March 1971," says Robinson, "and seeing the next band due to go on, heavily made up with mascara etc. It was the first line-up of Split Enz.”

By May they were in the studio, recording for Kiwi Records, who had set up a new Tamburlaine-focused sub-label: Tartar.

“We got signed up ridiculously easily by Tony Vercoe at Kiwi Records,” says Simon Morris. “He was a lovely old chap, and he promised us not only an album contract – recorded at a real studio, EMI, with a real producer, Alan Galbraith – but our own label, you know, like Apple. And the spirit of The Beatles was all over the first album – even the title Say No More was a running gag in the movie Help. We’d write a song, arrange it, then embellish it with overdubs. Alan Galbraith made sure it didn’t get out of hand – with one exception – and it was a lot of fun.

"We didn’t have a drummer at that stage, so Steve, who was the best rhythmically, did a lot of percussion – tambourine, bongos, tabla, that sort of stuff. I had the best ear for solos, so I’d usually do those – acoustic guitar, rudimentary piano, organ at one stage, and a bit of electric guitar. And Denis wrote the most specific songs, and brought some mates in to play strings and flute on them.”

“We had made a demo tape mostly of original material and this was shopped around to the various recording companies,” says Leong. “I was pleasantly surprised to get a call back from Tony Vercoe … Tony was planning to retire that year and he felt like doing ‘something out of the box’ with a final completely unexpected blockbuster. He had a twinkle in his eye when he gave me the numbers: there would be $30,000 available to record an LP in the EMI studios. Roughly speaking the budget allowed thirty hours of recording time on a lovely four-track machine, the very model that The Beatles had used to record Rubber Soul. There had been many surprises over the previous twelve months but this was right up there. We signed, somewhat in disbelief.”

Say No More is simply astonishing, and rightly recognised in Nick Bollinger’s 100 Essential New Zealand Albums. Robinson won the 1972 APRA Silver Scroll for ‘Lady Wakes Up’ and for good reason: a simple, elegant arrangement with guitars, subtle flute, hand-claps and wood block grace the homely homily: “In your woodbox of memories, may I be a chip.” When Julie Needham’s fiddle comes in during the opening to ‘Raven And The Nightingale’, it briefly foreshadows Alastair Galbraith’s violin on The Rip’s ‘Starless Road’, 15 years into the future.